How a Backlash against Gay Pride Helped Mobilize Grassroots Christian Nationalists, the 1978 edition

Or, why we should think of "backlash" not as a force of nature, but as the consequence of political mobilization

These days we’re quite familiar with conservative media and political figures amplifying and capitalizing upon anti-LGBTQ bigotry in order to gain more attention and support for themselves. Yesterday in the archive I came upon a 1978 example of this tactic that has much to tell us about how we got here, and also how we should (and should not) think about how “backlashes” (like the one we seem to be in the midst of) work.

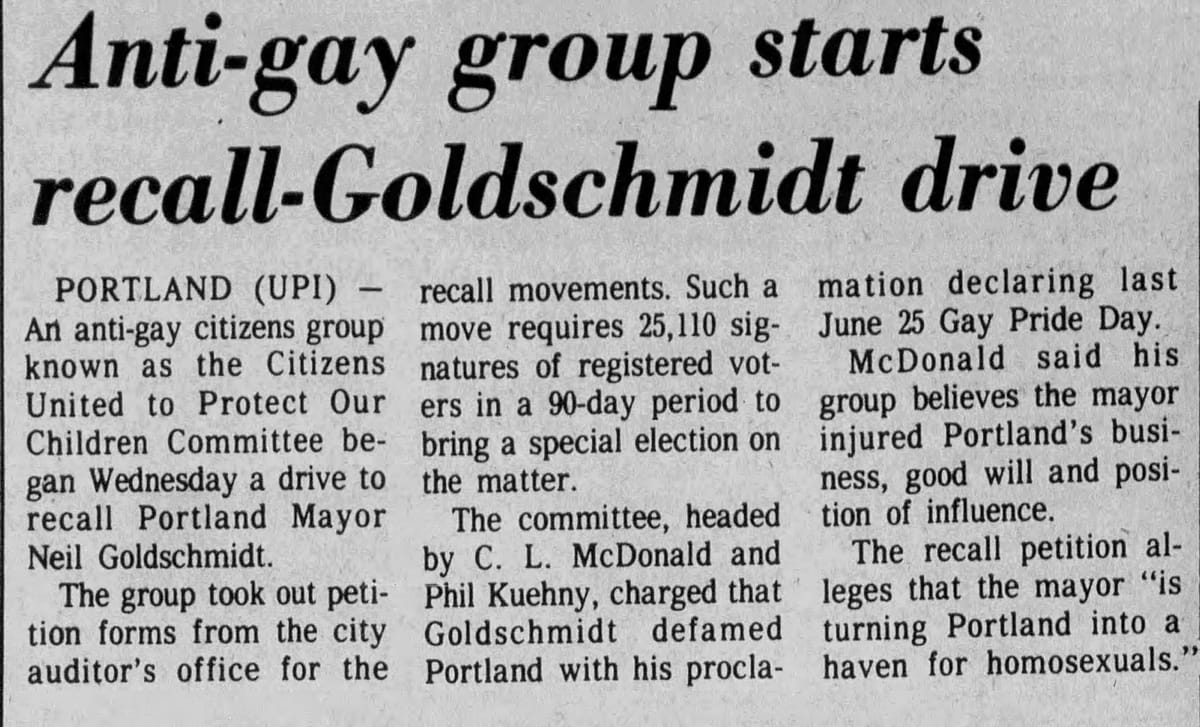

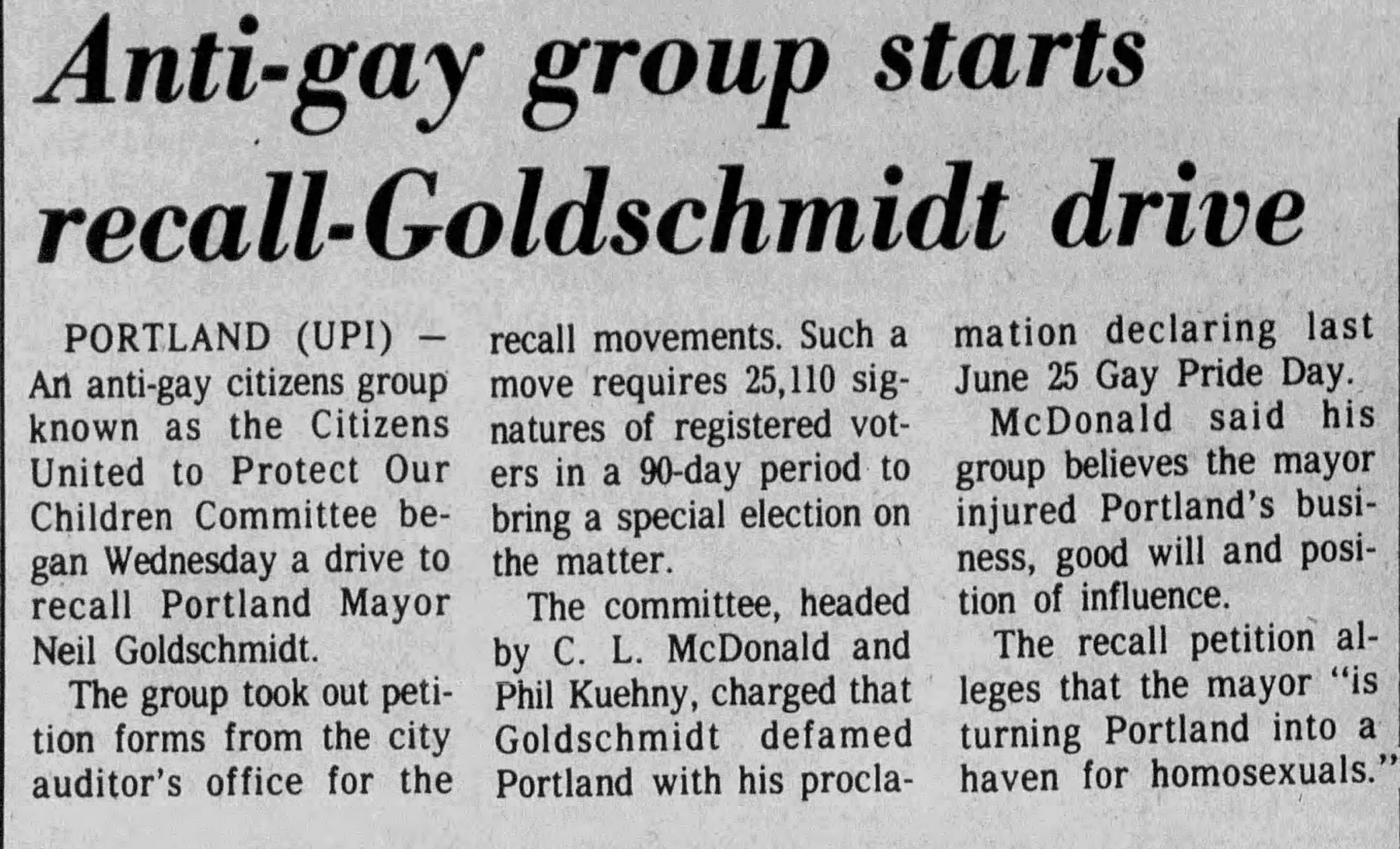

In 1977 Portland Mayor Neil Goldschmidt issued the city’s first Gay Pride Day proclamation. In response, a local group of conservatives, inspired by Anita Bryant’s outspoken homophobia, started a petition drive to recall Goldschmidt. It didn’t succeed, but it did generate a useful list of Portlanders who thought that a declaration of Gay Pride Day was a recall-able offense.

Rightlandia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

[Salem] Capitol Journal, 21 July 1977.

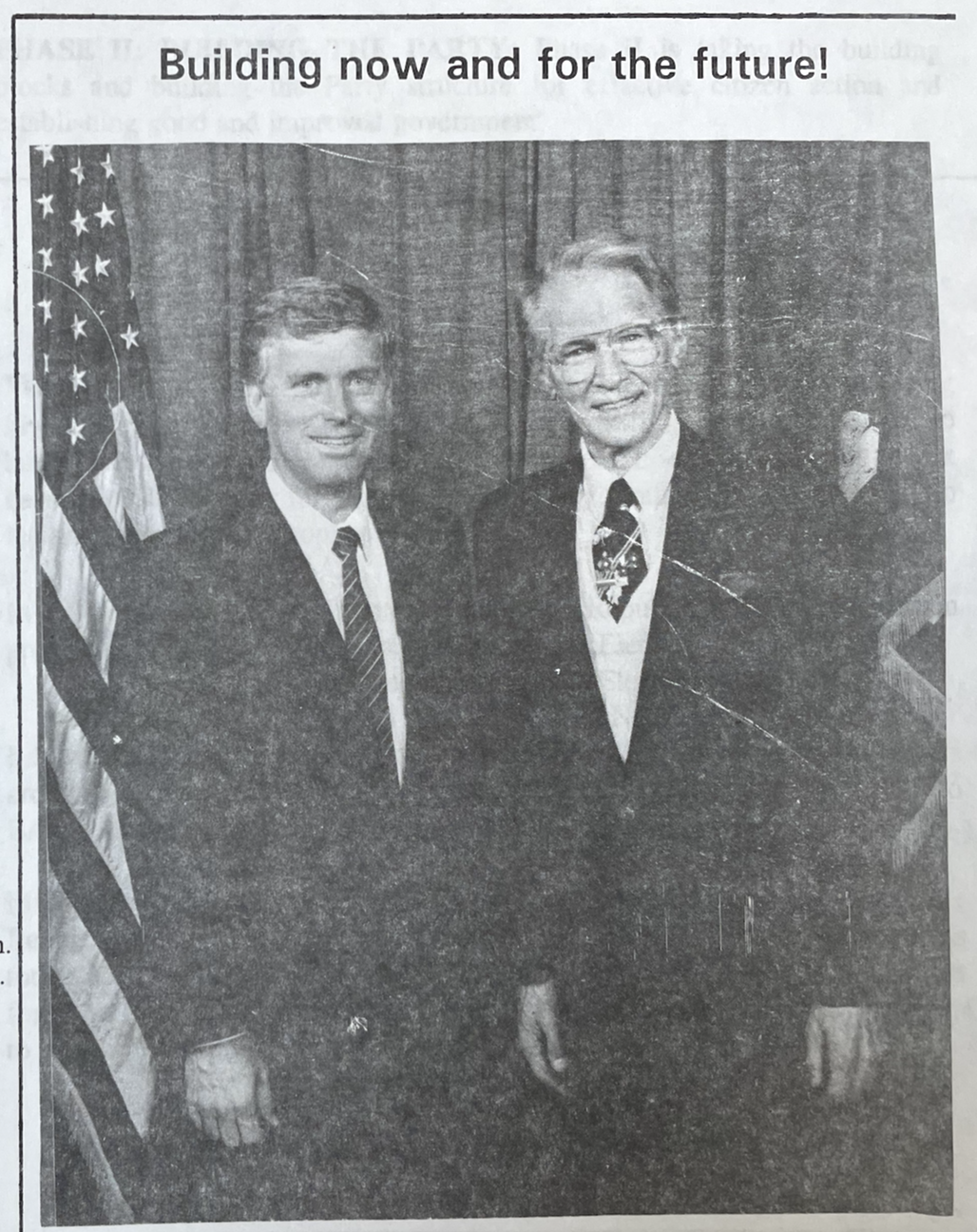

Walter Huss was, of course, involved with this recall effort. In 1977 Huss’s energies were focused mostly on his grassroots, insurgent campaign to become the chair of the Oregon GOP. He’d been working at this since 1968, recruiting far right precinct captains in every county and then encouraging them to send Huss-supporting delegates to the semi-annual GOP state convention. Huss fell short in 1968, 1970, 1972, 1974, and 1976, but he’d gotten a bit closer each time. All he needed was to find a few more grassroots conservatives willing to go to the state convention and cast a vote for him and against the candidate hand-picked by the moderate “establishment.”

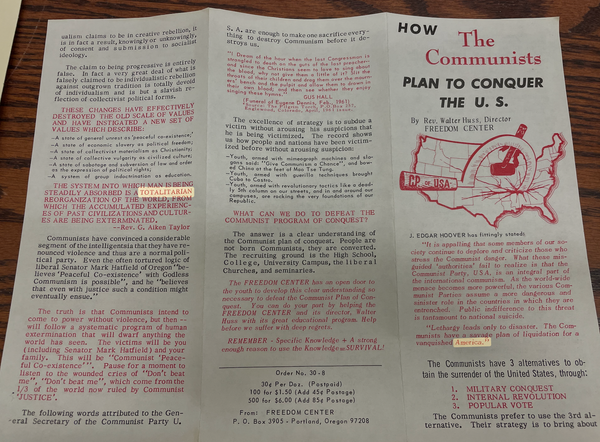

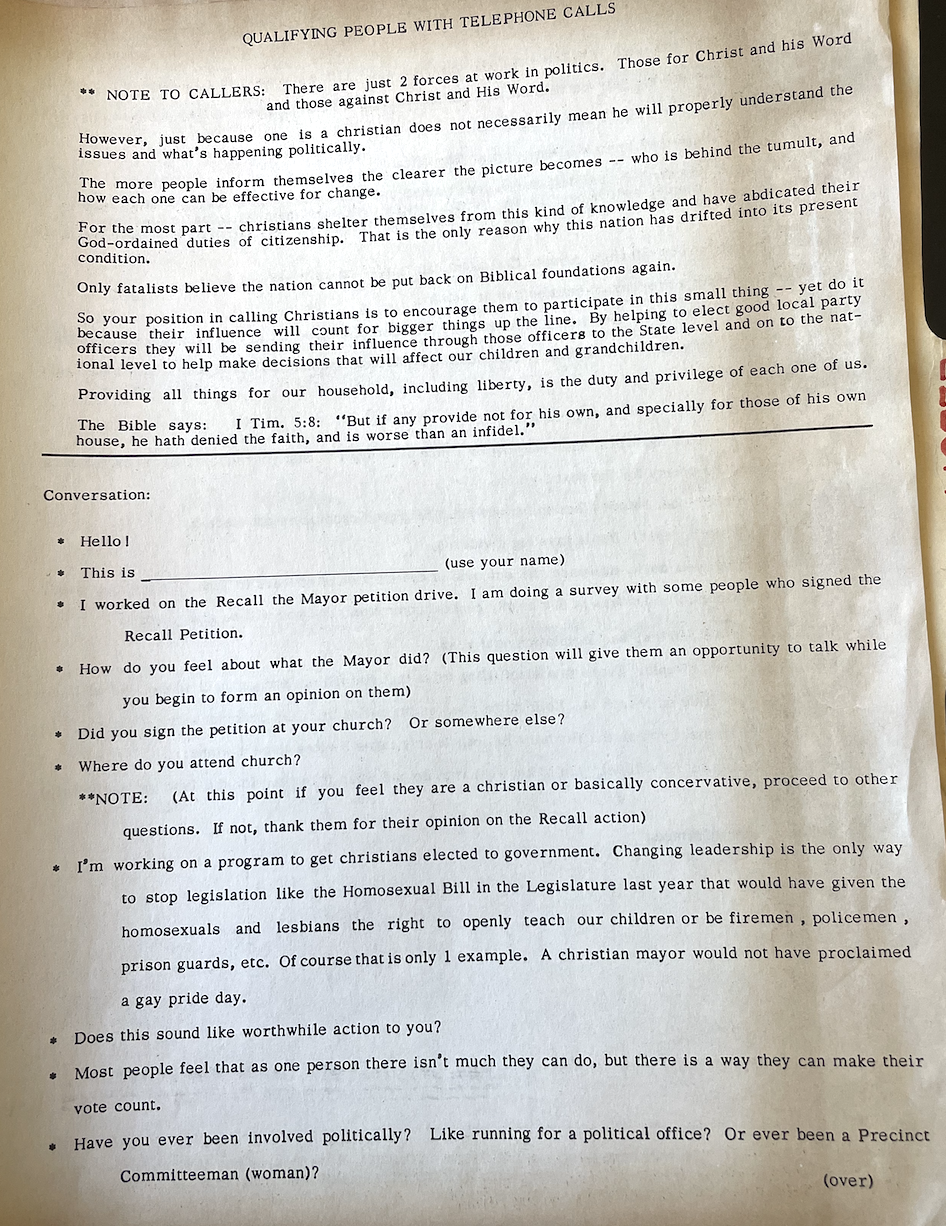

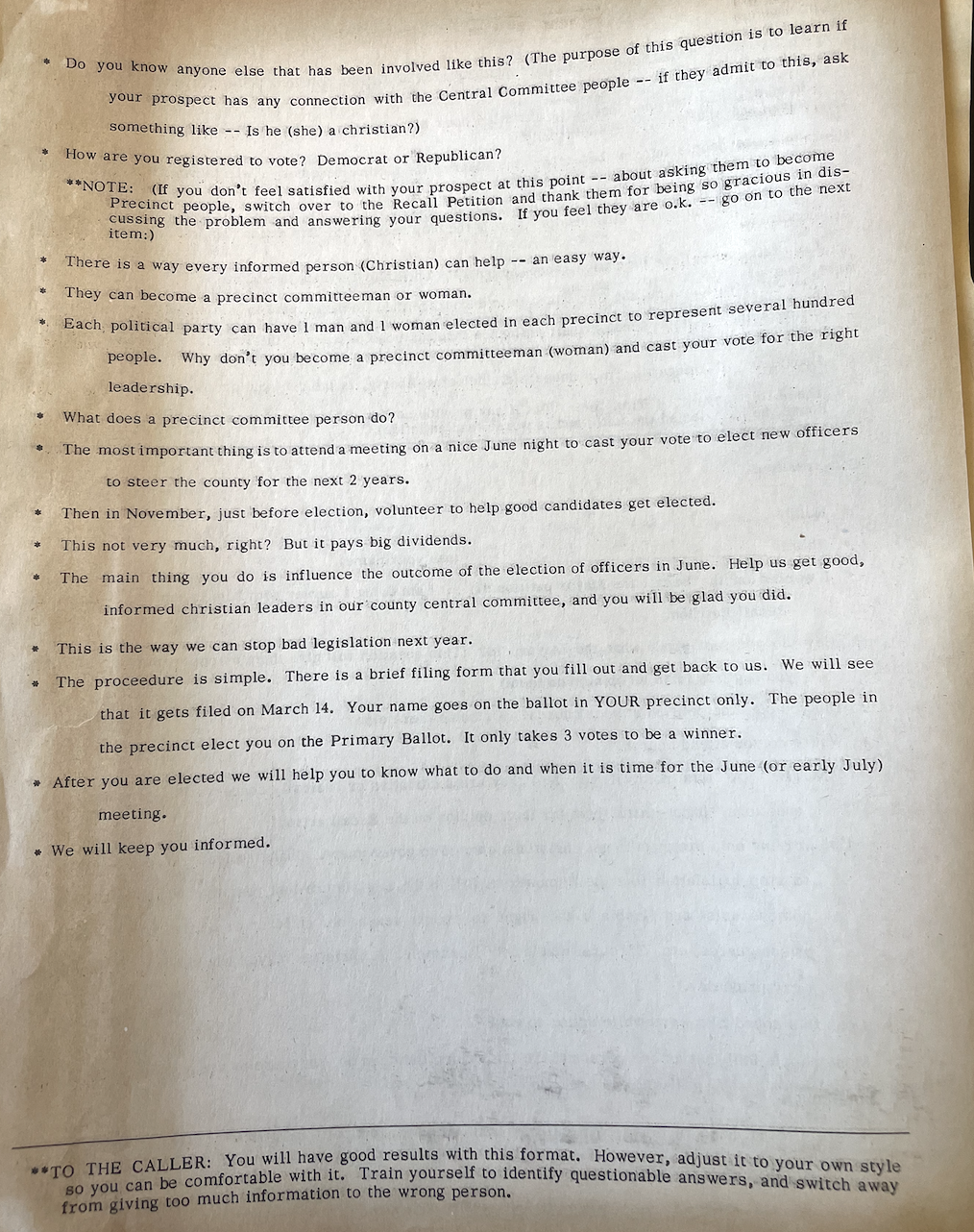

So Huss created a phone script he and his supporters could use to recruit Portland homophobes (and more specifically, Christian homophobes) to channel their recently activated anti-Gay Pride animus into the sort of concrete political action that would buoy the political fortunes of angry Christian Patriots like Huss. The ultimate goal was to take over the Oregon GOP from the more socially liberal Country Club moderates who had historically dominated it.

This document (which I found yesterday in the archive) adds important context to a key component of the public conversation about Huss’s elevation to GOP chair in 1978.

The local press coverage in the weeks following Huss’s surprise victory focused primarily on a comment he made at the convention about preferring “Christian” candidates. Vic Atiyeh, the 1978 GOP gubernatorial candidate who was Arab-American, publicly criticized Huss’s statement—claiming it was a slur against Jews and other non-Christians.

Huss defended himself by saying he didn’t mean to exclude anyone, but that, as a man of the cloth, he merely hoped everyone would become a Christian and a Republican and that he simply preferred Christians because he thought their morals were in the right place.

If you’re a regular reader of Rightlandia, you’ll know already that Huss’s claim to not be a bigot is hogwash. He was a rabid antisemite and white nationalist who thought the supposed Jewish/Communist Conspiracy was the malign force responsible for everything that was wrong in American society. But here’s the thing, people like Atiyeh may have had their suspicions about Huss’s fascist inclinations in 1978, but if they knew just how much of a hateful bigot he was, they clearly did not feel comfortable coming right out and saying it in the press. And so Huss emerged from this kerfuffle with the kind of plausible deniability that a lot of “Christian Patriot” extremists like him were granted in the late 70s and early 80s when fundamentalists were becoming more politically active in the Republican Party. Huss presented himself as a devout Christian who just thought Christians like him had the sort of moral compass that made for good political leaders—what’s so terrible about that?

That phone script I found yesterday gives us insight into the inner workings of Huss’s political organization that Atiyeh, the press, and other outsiders did not have in 1978. What we see there is not a sunny vision of benevolent Christians seeking to bring America into line with Jesus’s loving vision—it’s a call to arms in the context of a Manichean struggle between the forces of light and darkness. What we see in this document is Huss identifying people who share his Christian hatred/fear of LGBTQ people, and then encouraging them to translate that exclusionary animus into political action. This is how homophobia as a broadly dispersed social attitude gets transformed into a political force…this is how how “backlashes” get produced.

Huss did not convince anyone to think differently about LGBTQ folks. Rather, he sought to organize pre-existing white Christian discontents of various sorts (racism, homophobia, sexism, anti-immigrant animus, antisemitism, etc.) into a movement that could “take back our country” from the supposedly “anti-Christian” and “anti-American” forces that he and his supporters thought were in the drivers’ seat. Huss knew that having the right attitudes wasn’t enough. Christian Patriots needed to gain political power and the Republican Party was their chosen vehicle.

As historian Larry Glickman discusses in this great article on the racist backlash of 2020, “backlash” is a recurring theme and dynamic in US history. But while backlashes are a very old and familiar phenomenon, there’s nothing inevitable or natural about them. Backlashes are political phenomena that result from concerted organization on the part of those who seek to benefit from them. And even if backlashes don’t achieve their concrete political aims, they mobilize and organize grassroots reactionaries by giving them a focus for their anger, an organization to join, a business to boycott, a vice that they can signal to others as a badge of belonging to a movement of “real Americans” who want to “save our country.”

That mode of being and belonging—that straight white reactionary identity politics—has become a central dimension of the GOP’s political culture in the age of Trump. But as the story of Walter Huss and the Oregon GOP shows, that grassroots insurgency and it’s quasi-fascist culture of “participatory anti-democracy,” has been a long time in the making with a playbook that has remained fairly constant. This reactionary political culture requires care and feeding, it requires the work of local people like Walter Huss and nationally-known figures like Anita Bryant to organize inchoate fears or anxieties into a coordinated political force capable of successfully lashing back at some perceived threat.

In the 1980s and 90s Walter Huss was remembered in Oregon, to the extent that he was remembered at all, as a pathetic failure, an eccentric vestige of a bygone era. Anita Bryant’s national reputation suffered much the same fate. But as we can see by the continued presence of organized anti-LGBTQ bigotry, the reactionary political culture they nurtured and fed did not vanish.

Walter Huss lost every single political battle he fought [like for real, over 40 years he ran for office about a dozen times and put forward dozens of petitions and ballot measures and every single time he lost by wide margins], but ultimately, his vision of the Oregon GOP ended up triumphing. In the late 1990s Vic Atiyeh, Mark Hatfield, and several other old-school moderate Republicans would gather for a regular meeting at a Salem restaurant where they’d bemoan the sorry state of the ever more radically right Oregon GOP. They affectionately called themselves the “Old Coots.” Little did they know that the “old coot” most responsible for rendering them politically irrelevant was a guy named Walter Huss who they universally dismissed as an irrelevant kook. And little did they know that while they were eating pancakes, drinking coffee, and reminiscing about the good old days when Republicans could win elections in Oregon, Walter Huss (approaching the age of 80) was driving his 1982 RV around the state drumming up grassroots support for his latest tax reform measure that failed to get enough votes to win, but fired up yet another generation of reactionary Christian Patriots like him who called the OR GOP home.

Rightlandia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.